A Brief History written by Betty M. Adelson

Even before there was a written history, dwarfs appeared in the artwork of many cultures. Images of dwarfs are among the oldest artifacts extant: They are depicted in ancient stone and clay funerary sculpture in Egypt, India, China, and the Mayan civilizations; they are highlighted in the legends and myths of every nation.

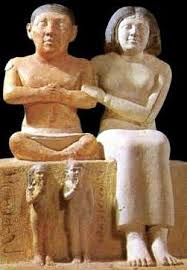

Seneb and his wife, a 4th or early 5th Dynasty dwarf. He was overseer of the palace dwarfs, chief of the royal wardrobe and priest of the funerary cults of Khufu.

In the courts, from ancient Egypt through the 18th century, dwarfs were collected, indulged, sometimes abused, and sent by royalty as gifts. In ancient Egypt, dwarfs were associated with Bes and Ptah—gods of childbirth and creativity—which helped enhance their status. The Egyptian courts were unique in that they offered roles to dwarfs as priests and courtiers, as well as jewelers and keepers of linen and toilet objects.

Monarchs in all nations sent emissaries far and wide to gather dwarfs: Although some may have been free, it is likely that others were held in some degree of bondage. A combination of being highly prized, but the property of an owner, were among the defining characteristics of dwarfs' lives during the nearly 5000 years they are known to have been present in the courts of Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central America.

In all periods, they were assigned to wait upon or amuse others. The nature of each court differed, however, reflecting the temperaments of its ruler and the character of his subjects. Famously present in the courts of ancient Rome, dwarfs gratified royalty's appetite for violence and lasciviousness. In the reign of Domitian (81-86 AD), they were matched with Amazons as gladiators, and wealthy women selected their favorite dwarfs to take home to participate in erotic games.

Paintings of Velasquez, Francesillo de Zúniga

By the time of Isabella d'Este, Marchioness of Mantua (1474-1539), a very different atmosphere prevailed. Her attitude toward her dwarfs resembled her attitude toward her other unique valuable collections—like classical writings, paintings, gold and silver objects, and majolica. She could present them as gifts, or lend them to relatives for their amusement. It must be acknowledged that some court dwarfs, like painter Richard Gibson (1650-1690) in the court of Charles I of England, were better off than those outside the court—offered good food and clothing, and provided with artistic training. However, even in the benevolent, family-centered courts of Spain, famous later for the superb paintings of Velasquez, Francesillo de Zúniga, clever 16th-century court dwarf of Carlos V, could be murdered, allegedly in retaliation for his sarcastic critique of a courtier in his Cronica Burlesca, a rare work by a court dwarf (de Zuniga 1989).

Only a few commentators have analyzed the role of dwarfs in the courts—most notably anthropologist Francis Johnston (1963) and humanist geographer and theorist, Yi-Fu Tuan (1984). While Johnston saw the status of dwarfs as generally diminished since the court era, reduced to handicapped status by their medicalization, his view of their previous position was somewhat romanticized. Tuan's 1984 analysis is far more insightful. He perceives dwarfs as constrained by the same combination of dominance and affection as other groups—including animals, women, black slaves, fools, and castrati—treated as pets, and similarly indulged or exploited.

With the decline of the courts in the 18th century, dwarfs began to be exhibited more frequently at fairs, sideshows, and taverns, as well as continuing to appear at private levées for the nobility. Polish court dwarf Joseph Boruwlaski (1739-1837) was a "bridge figure": He left court when he was refused permission to marry his average-statured love. He supported himself and his wife and children by exhibiting himself and playing the violin throughout Europe, in as dignified way as he could manage. He ended his long life in Durham, England, dependent upon the charity of patrons. One of a very few dwarfs to write a memoir, he observed that had he been formed like other mortals he could have subsisted by means of his energy and labor, and been acknowledged as "a man, an honest man, a man of feeling" (Borulawski, 1778, p. 247).

Charles Stratton and Lavinia Warren

In the 18th and 19th century, exhibiting dwarfs alternated between this activity and "straight" often low-paying occupations such as watchmaker, seamstress, or bookkeeper. Charles Stratton (Tom Thumb) and his wife, Lavinia Warren, were among the greatest celebrities of the 19th century, hosted on their honeymoon by Abraham Lincoln. Well into the 20th century, sideshows, midget villages, and traveling troupes performing musical extravaganzas were popular, perpetuating the illusion that happy communities of very short people were naturally occurring phenomena.

This period has been expertly researched and described by Robert Bogdan in Freak Show (1988) and documented in photographs in works such as Hy Roth's The Little People (Roth & Cromie, 1980). One New York reviewer's "compliment" to the Liliputian Opera Company at the turn of the 20th century captures the unfortunate situation of the best "freak" performers: "Adolph Zink was so exceptionally able that it is to be hoped he may grow up some day and act without the necessity of posing as a natural phenomenon" (Goldfarb, 1976, p. 279).

Dwarfs were the favorites of agent Nat Eagle, who made much of his living by maintaining a company of eight or nine Little People. Beginning with the Chicago World's Fair in 1934 and continuing as late as 1958, he and Mrs. Eagle created a familial atmosphere, spending much of the year with them in Sarasota, Florida. Like court dwarfs, "Eagle's midgets" are portrayed in a New Yorker article as less than full adults, requiring a patron to shepherd their lives (Taylor 1958).

The Ovitz family from Transylvania

During the same era, the Ovitz family from Transylvania, consisting of seven siblings with a condition called pseudoachondroplasia and their three average-statured siblings formed a self-managed troupe; they toured Europe and, after World War II, performed in Israel, offering dramatic, comic, and skilled musical performances. The remarkable story of this group, who survived Mengele's depredations in Auschwitz, has recently been published (Koren & Negev, 2004).

Although large traveling companies and midget villages have disappeared, and sideshows are rare, even today dwarfs continue to be sought after for various peripheral entertainment venues, usually more for appearance than talent. Dwarfs' appearance and mythological associations continue to arouse fascination and ambivalence, often causing them to be "[reduced] in the minds of strangers from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one" (Goffman 1963, p. 3) —in fact, liable to be viewed as corresponding to all three of Ervin Goffman's stigmatizing categories: physical deformities; unnatural passions and dishonesty; and tribal stigma.